Between lucidity and irony, “Millones al horno” (“Millions in the Oven”) reveals the talent of a journalist who turned the newspaper column into a literary gem. His writing—light, precise, and sharp—transforms the everyday into an x-ray of the modern soul.

By Jorge Alonso Curiel

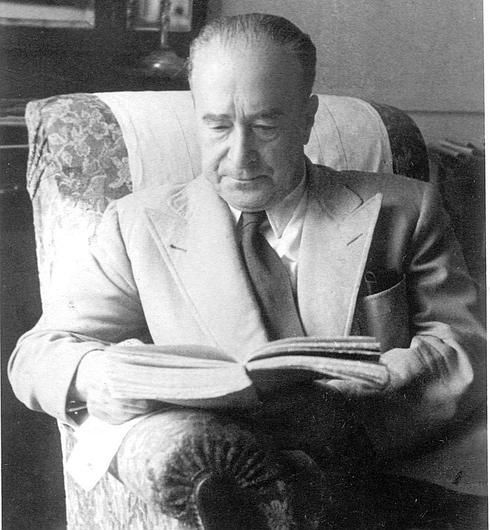

HoyLunes – Without solemnity, without dogmas, and with simplicity, clarity, wit, elegance, lucidity, critical insight, and humor, “Julio Camba” (Pontevedra, 1884 – Madrid, 1962) became one of the most brilliant columnists and chroniclers of his time. He knew how to capture and portray the spirit of the age he lived in and has remained a key reference in journalism, influencing countless writers who followed.

Also the author of a novel, short stories, and travel books, this expert gastronome—whose life was as fascinating as his work—stood out above all in the brief yet demanding format of the newspaper column. Time has placed him among the classics, because anyone wishing to devote themselves to this craft should read and continually learn from him.

A Cosmopolitan Galician

Julio Camba was born into the modest home of a baker. Still a teenager, he left Galicia as a stowaway on a ship bound for Buenos Aires. There he began his journalistic career by writing anarchist pamphlets. That bohemian stage of idealistic struggle and rebellion taught him many things—above all, that the best way to be in the world is to laugh at it, not to take it too seriously. This truth is constantly evident in his writings.

After being expelled from Argentina, Camba returned to Spain and began writing for *El Diario de Pontevedra*. Soon after, he settled in Madrid, where he collaborated with anarchist publications and even founded his own newspaper, “El Rebelde” (“The Rebel”). In 1905, he joined the staff of “El País”, and two years later he worked as a parliamentary reporter for “Nueva España”. In 1908, he began his life as a foreign correspondent—writing dispatches more literary than informational—for “La Correspondencia de España”, covering the political change in Turkey. Upon his return, he joined “El Mundo” and later traveled to London and Paris, from where he sent his chronicles. In 1912, he signed with “La Tribuna” as correspondent in London and Berlin. And in 1913, he was hired by the monarchist newspaper “ABC”, where he would write until his death—except for a ten-year period, from 1917 to 1927, during which he worked for “El Sol”.

Humor as Intelligence

Published in 1958, “Millones al horno” gathers a selection of articles written for “El Mundo” between 1910 and 1912 in Paris and London, as well as some written for “La Tribuna” during his time as correspondent in the British capital from 1912 to 1913. These were the turbulent years between wars, when the world trembled between economic crisis and political confusion—yet Camba did not write from tragedy, but from the everyday.

His humor was not that of cheap jokes or coarse sarcasm, but an intelligent, elegant wit—light, critical, skeptical, and precise—that made readers both laugh and think. Camba observed modern man as one might observe an experiment both amusing and slightly tragic. “The world is divided between those who believe in something and those who believe in nothing—and both are wrong”, he once wrote.

In “Millones al horno”, he plays with the metaphor of money as an ingredient that, when poorly cooked, can ruin our lives. Its title—both domestic and philosophical—summarizes his view of the world: progress and wealth can easily become forms of dehumanization.

The Master of the Short Article

Camba turned the newspaper article into a literary form in its own right—his natural territory. His prose, as light as it was precise, radiates charm, allure, and readability. And “readability” may be the defining word to describe him, because that is the secret of great writers—and one not all possess. His columns, though published daily, were written without haste, with pause and reflection, achieving pure literature through digression and observation.

Reading “Millones al horno” today is to discover that his ironic articles could have been written this very morning. Everything within them remains current; they mirror the same bewilderment of contemporary man. The digital world of today would find in his gaze an excellent antidote. He, who wrote from hotels and consulates, would have delighted in dissecting the contradictions and advances of our time.

The Man Who Lived in a Hotel

Camba died in 1962, in Madrid, in the same room of the “Hotel Palace” that he had made his home. There, surrounded by books, newspapers, and breakfast trays, he wrote his columns for years. When asked why he lived in a hotel, he replied with one of those phrases that perfectly summed up his philosophy: “Where could one live better than in a place where they make your bed and bring you coffee?”

Dear reader, step into the world of this unclassifiable, boundless writer—provocative yet ironic (“Write short, and get paid long”, was his advice to young writers)—who created his own genre and, fortunately, never stopped writing, even though he often claimed that the true triumph of writing was to stop writing. Seek out “Millones al horno” and discover the literary brilliance—the great literature—of a writer of newspapers.

#hoylunes, #jorge_alonso_curiel, #joyas_de_papel, #julio_camba, #millones_al_horno,